Two years away from the U.S. and here I go again, this time on a plane from Frankfurt to Seattle. It’s one of those big planes, identified by large numbers and a letter or two, but I never go for those details. Some people obsess over them, as if they could fly the plane in an emergency, but only if it’s a Boeing-737 and not a Boeing 777X. The best part of this flight is there are only 30 people onboard, which gives me three empty seats and enough room to spread out books, a notebook, and eventually myself. These flights are long, but 11 hours with three empty seats and one drink is almost agreeable.

Last night while eating a chicken salad in a hotel restaurant, I tried to make sense of another journey into the world. Not much came to me. Mostly I watched people. There were people coming in and out of the restaurant, people eating, people visiting over beers. It’s odd how you see people visiting over beers but seldom over spirits or cocktails.

Because this was a hotel restaurant near the airport, almost everyone in the place was a traveler. There was an eastern European couple, plus one. The men were large and heavy. The woman who between them was skinny and maybe in-shape from the fit of her blue jeans. The men ate shrimp and drank Coca-colas. The woman sipped at a lemon soda and nibbled a salad. Her salad didn’t make me feel any better about mine. I had the thought that I should be eating meat instead of Romaine lettuce. There was an American couple. They dressed badly, and their faces looked stressed. There were predictable clusters of Scandinavians who were predictably well-groomed and indifferent to everyone in the restaurant. The guy waiting on me was from Lithuania. His name was Lukas. He told me he was pulling an extra shift. I wasn’t surprised. Eastern Europeans who live in western Europe work the extra shifts. Lukas said he was trying to make back money because of funds he had lost during COVID. He said he had needed a couple of loans to pay his rent. Now he was paying off the loans and the rent. This was Oslo, too. There’s no such thing as a deal in Oslo.

After the salad and a liter of water, I walked around the hotel. The lobby had a fireplace and pretty windows trimmed with birch wood. Over the gas fireplace there was the ubiquitous television set, broadcasting BBC World News. The news amounted to starvation in Afghanistan, a revolt in Sudan, the president of Brazil apparently had a Facebook post removed in which he was trying to link COVID vaccines with AIDS (?), the Biden administration plans to require proof of vaccination to enter the U.S. if a traveler arrives from a country where there are high vaccination numbers. However, no proof of vaccination will be required if a person arrives from a country where there are low vaccination numbers. I watched the news cycle for two or three minutes. What to think? Either the world, the news, or both are collective shit piles. The other thought is I live on the edge of a sund in a cold climate without a television set, and, given this fact, it remains curious to see the world going up in flames in such beautiful colors.

When I left home, I flew on a crowded plane and no one wore a mask. We’re all doubly vaccinated. We’d all recently taken a COVID test that read negative. I didn’t catch a whiff of trepidation. I was alert for it, too, the way a dog is alert for its owner dying. But no trepidation, just folks on a plane. Now that I’m out in the world, I sense those of us who live in the Arctic Circle had a different experience during the pandemic. It’s cold in the Arctic. Everyone socially distances as a way of life. Also, no one wants attention in the far north. As a neighbor told me, “life is not for amateurs.” Which I take to mean life is destined to fall apart and only the pros among us reach the end with minimal damage. And I’m not talking about the big tragedies of life of either. I’m talking about a myriad of inconveniences and sabotagery, intended, one can believe, to make every trip to the mailbox like a barefoot walk through a thorny field.

To my own point, the EU immigration authorities were not sure where I lived. The guy scanned my passport and looked at me and looked at his computer and looked at me again.

“Do you have other documentation?”

“Like what?”

“Like another passport. Where do you actually live?”

I told him my best guess and handed him more paperwork. He shrugged and stamped my passport and off I went. I felt relieved. I thought of having another gin & tonic to celebrate, but the last one was thin and cost 12 American dollars. A gin & tonic has become a drink of choice while in travel mode. A good gin & tonic is bright and cold with warm hints of juniper. It will pierce through the accumulated gristle of paperwork, unknown citizenship, fear that one of the four planes I will ride in the next 24 hours will crash. There are the nagging life questions. Who am I? Is there deeper meaning to our experience? Is there ever a point when our efforts seem satisfying? Mercifully, a gin & tonic can nullify these concerns. While I have no desire to reach the numbing “click” of a Brick Pollitt, I don’t mind dulling the edges a bit.

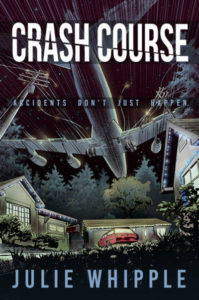

I also bring books to cheer me up when I travel. They are companions, and occasionally I’ll purchase a book from an airport bookstore. I do this because I hope bookstores will stick around in airports. Also, airport bookstores tend to feature current and popular titles. I read comparatively little contemporary writing, though I am not oblivious to it. Airport bookstores are solid for what people are reading. I purchased Milan Kundera’s The Festival of Insignificance in Oslo and Paul Hendrickson’s Hemingway’s Boat in Copenhagen. I picked-up Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens in London (Gatwick) and Fannie Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café in Houston. The latter purchase was a long time ago. I wonder where I was going. In the two empty seats next to me, I have stacked a modest pile of books, unsure of what I might want to read. I have a copy of Crash Course, written by my friend Julie Whipple. Julie is from the Pacific Northwest and, consequently, the place where I am traveling. I find familiar moments nicely framed in her work. Here is an example:

The hip destination city of Portland today is a far cry from the mostly-ignored, mid-size metropolis it was in 1984. If a Portlander traveled abroad—or even to New York or Chicago—and someone asked where she was from, the sensible answer went something like this: “’You know where San Francisco is? And Seattle? Portland is in between those two in Oregon.’” There would be a puzzled pause as an unexpected state—Oregon—appeared on the map in the questioner’s mind’s eye; and then it wasn’t uncommon to get the sudden ah-ha, “’Oh, yeah; I heard it rains a lot there.’”

Julie’s book concerns the crash of United Flight 173, which is not the most comforting read while plane hopping over two continents and the Atlantic. The other books I have with me are Andre Tarkovsky’s Sculpting in Time, Anslem Kiefer In Conversation with Klaus Dermutz, and Ryszard Kapuscinski’s The Shadow of the Sun. Kapuscinski’s book is rich in its language and tease, such as, “One can’t afford to be less than a great expert on the geography of these paths. Whoever knows them less than well will lose his way, and if forced to wander too long without water and food will of course perish.” Kapuscinski’s book was recommended to me by a friend, by someone I respect as a reader, though I wish knew more of how certain works, including those of Kapuscinski, touch her.

Although I dabble in all three books, I have mostly settled into the Kiefer book, which concerns, among other topics, the relationship between art and theology. Both subjects open wide doors, such as Keifer’s reflection on snakes:

“I’m most fascinated—and terrorized—by snakes. I’ve always had both a strange phobia of snakes and a strange fascination with them. I once bought a boa constrictor and put it in a large terrarium. I thought I could overcome that phobia. You can keep snakes as pets, like a watchdog. When you can tell them properly to go in the corner, they go to the corner. I could never bring myself to touch a snake. It was a catastrophe. Snakes are mythological creatures. In the Old Testament, there are constantly snakes, bronze snakes. And the miracle before the Pharaoh: turning a staff into a snake. The image of the snake has been engraved in our cerebellum from time immemorial. That’s why we cringe when we see a snake. It’s not a conscious reaction.“

Additionally, and of special interest to me, Keifer reflects on the concept of homeland. He reminds us, “Heimat, homeland, is something you carry with you. Homeland is not something that is bound to a certain location, which you leave and return to, but something you carry with you, in your memory.”

I appreciate Keifer may be toying with us or with his interviewer, as heimat is a knotty term in Germany. The word, although not quite translatable in English, denotes a homeland or homeplace, as in where one is born or where one has legal status, but it also connotes a patriotic impulse, invoking questions of who belongs and who does not belong to the heimatland. The word is also a romantic one, and I tend to lean with the Romantics.

Twice in my life the world has profoundly opened for me. Twice I have stood in its wonder. And here I am, returning to the U.S. to screen a film and to spend days with my filmmaker friend, Charlie Pepiton, and to work with my painter friend, Tabby Ivy, whose paintings again and again enter a homeland. Yet I go on asking, where is the homeland I can claim? I do not have a convenient answer, yet I often find myself more at home on good ground than in a nation. I can use the Norwegian word jord to suggest my meaning. To be at home on a land, on ground, on an earth, and to be outside the question of where is my homeland, is to be at home.

Typically, I do not relish sitting in a window seat on a plane. I much prefer an aisle seat. With an aisle seat, I feel like I can escape, I can stretch out my legs. Both of these allow me to relax a little. Though today, with the empty seats and the window right there, I took a look outside. We were flying over Greenland! The sunlight shone clear and bright and struck the sea more sharply than the snow-covered landscape. I could see horseshoe bends of frozen country that reminded me of the gooseneck canyons on the Green River. Not all of the canyons were snow-covered. Near the summit there were slabs of grey stone, and in the lowest reaches of these canyons were veins of what looked like river basins. Thin blue lines of recent blue ice pushed into the sea. There was a vastness. I scanned the shores for villages, but there were none. For a second, I could have believed I was seeing another earth. I kept thinking what I would say if I were down there, hiking or sitting on one of the few snowless rocks. It would have been something like, “Well. It’s cold.” Or maybe, “Here we are.” All that cold and snow down there. The sea and bright sun. “Here we are.”

I am still hours from the U.S. and Seattle and then another plane to Spokane. But I got time. I can read more. I can go on scribbling in my notebook. I can watch a couple of movies. I haven’t seen Nomadland or The Father, and people who talk about movies talk about both of these films. I feel like I have to orient myself before I can go on with anything, before I can go on reading or watching a movie. I know when the plane lands, I will feel the buzz and throb of people. I will feel their anxiousness and relief. Most people will be in a hurry. Even those of us pretending to be calm will contain some shiver of anticipation. Soon enough, we’ll all be standing in a long immigration line, waiting our turn to approach an entry counter, where we will be asked to show our faces and paperwork. I will be at the counter, too. The immigration officer will look at my passport and photo. The officer will then insist that I focus my eyes on a small camera fixed to a window dividing us. There will be that question, too. “Where do you live?” I will stare at the officer. The officer will stare at me. How to answer such a question?