The essay you are hopefully about to read is part of my forthcoming 2022 collection and exhibition with the Montana artist Tabby Ivy. Both the collection and the exhibition will be called Between Artists: Life in Paintings and Prose. The exhibition will take place June next year at the Hockaday Museum of Art in Kalispell, Montana. I hope you all, and I do mean all of you, can be there. The piece that follows describes a morning last summer, when, after seeing one of Tabby’s paintings, I bicycled to a local river where I fished for sea trout and salmon. The story is not, however, of my most recent fishing trip, which I returned from late last night—five days spent in the very Far North with four seasoned Norwegian fishermen. Maybe that story will come around someday too.

July 8, 2021

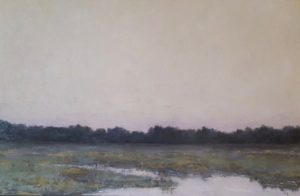

A couple of weeks ago, Tabby sent a new painting to me. The painting is called “Contented.” The morning I received the painting, I was preparing to ride a bicycle 12 kilometers down the road to our local river. This same river, three months prior to my ride, had been buried under ice—a reminder our local landscape is one of spiky extremes. My plan was to camp along the river for a couple of days. I wanted to fish for salmon and seatrout and to work on a few bushcraft skills. But also, I wanted to be alone. My gear stood packed beside the door, the kitchen had been tidied, the carpets vacuumed, and the oven dials had been switched to zero. All that accomplished, I checked my computer one last time before setting out that morning. That’s when I saw Tabby’s email. That’s when I saw “Contented.”

The painting is of three cows standing in a field. There is a black cow, a brown cow, and another that looks like a dairy cow. There is tall grass and rich textures, leading us from the foreground towards two shelves of deep woods and a final, distant treeline, all of them settled beneath one of Tabby’s grey skies. The trees, as they often do in Tabby’s work, cause us to stop and then to look beyond them. I cannot turn away easily from Tabby’s worlds, from her fields and trees. That being said, I typically do not look twice at animal paintings. The exception is sporting paintings. I am thinking of Richard Ansdell’s hunt paintings and Philip Reinagle’s dog and shoot paintings. For those of us who esteem sporting scenes and who are also sportsmen, such paintings leave out the troubles of the sporting life. We do not see a horse standing on someone’s foot, a hook caught in someone’s thumb, cold feet, cold hands, and shots and lines blown afoul by the wind. Instead, it’s all romance, pageantry and pastoral in the sporting works I enjoy.

Perhaps it is the lack of these elements—romance, pastoralism, pageantry—that motivated me to spend time with Tabby’s painting that morning. The painting does not seek to be or to do anything. It is not unusual for animal paintings to remind us of our own animals, which I will speculate is what many animal paintings hope to accomplish. Or, in the case of sporting paintings, to remind us of the best days. None of this applies to “Contented.” The cows do not especially blend into the field. This is markedly the case with the dairy cow centered in the painting. The black and white coloration of the cow stands in pronounced contrast to the colors of the field and to the other two cows, as though Tabby risks giving too much attention to this one animal. We have no idea whether the cows will linger in the field or wander towards us or the trees. They belong to themselves and unconsciously so.

I spent what time I could spare that morning looking at the painting and afterwards left my house. Outside, I pushed the bicycle up the path from our front steps to our mailbox at the top of the road. I then rode towards the river on what may have been the hottest day of the year. The painting, however, stayed with me. As I bicycled those 12 kilometers, I could not shake the sticky question intended with the title and perhaps with the painting itself. What does it mean to be contented? I was a riding a bicycle between mountains and on a road following the sea. Sunlight fell on the fields and barns. Neighbors waved. Isn’t this, I reflected, the very place of contentedness? I soon remembered my Aristotle and how contentment or eudaimonia arrives at death. Better go ahead and die then. This was the thought, as I saw myself surrounded by a Northern summer and light that rivalled Bowra’s Grecian sun. This, for me, was an occasion when any of us might tell ourselves that life can’t get any better.

Even so, I questioned how content any artist or writer should be. It seems that an artist must struggle to produce work, as humdrum as that idea has become. But to struggle doesn’t require a week-by-week or day-by-day existential pounding. Struggle can be as harmless as asking, “how do you paint this line” or “how do I write this sentence.” Thomas Mann recognized this when he wrote, “A writer is somebody for whom writing is more difficult than it is for other people.” Or, as Steinbeck reminds us, “there is nothing more intimidating than the blank page.” Take a muse. A muse, as the word itself suggests, inspires desire. To desire a thing implies we do not possess it. When Homer chants, “Sing to me o muse of the man of many twists and turns,” he seeks from the muse stories of Odysseus. He is also trying, with the help of his muse, to compose a poem, which he, Homer, most desires. Why? Because it will be a struggle to write the poem. Homer knows this. So, he better plead for help.

I kept pedalling.

On both sides of the road there were fields of wildflowers and hay. The days had been sunny for a solid week, and farmers had cut their hay and bailed it and wrapped their bales into white bands of plastic, which will maintain and ferment the hay. Round bales dotted the fields and the sund glistened with summer. I could smell the hay and a slight tinge of the sea. They washed over and through me. I was in this place, peddling through more countryside and life than I could take in, more than I could see. Still my mind went back to Tabby’s “Contented.” Our worlds crossed in her painting. Art had nudged its way into this, my ordinary life. I am confident Tabby carries her own story about “Contented.” I should like to hear that story someday.