Men and bits of paper, whirled by the cold wind

That blows before and after time

—T.S. Eliot, “Burnt Norton”

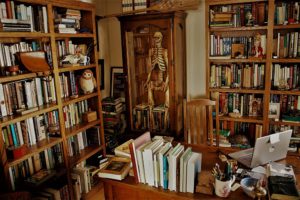

I enter the room and click on the overhead light. I drop my shower towel and sigh. Pants are somewhere. A shirt. My office is in shambles. Books are stacked on top of books. Books are doubled-shelved. Books behind books. There are scraps of paper on my desk, on the floor, on the bookshelves. Overdue bills. Letters from my father. Pads of drawing paper because I prefer to write on drawing paper. Wrappers from my daily dosage of anti-rejection medication. Two coffee cups, with the milky rings of what might have been coffee bonded to its circumference. Two trash bags stuffed into cardboard boxes from my previous effort to clean. An enormous reindeer antler that Charlie Pepiton and I discovered hanging from a tree this past summer remains crammed between a bookcase and the gun cabinet where Ed, the skeleton, resides. There are the usual bones, skulls, rocks, and tortoise shells lining the bookshelves, alongside knives, pipes, and duck calls. There are postcards purchased from corner shops in other countries.

Having extracted a shirt and a pair of pants from a pile of books and sweaters, I take survey of the volumes on the floor. Some of them have massed together. To the left of my desk is the complete works of Patrick Leigh Fermor, nested between Kinkos Kazantzakis’s Zorba the Greek and Lawrence Durrell’s The Greek Islands. To the right of my desk is a stack of recent War World I readings: Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That, The Missing of the Somme by Geoff Dyer, Memoirs of a Fox-Hunting Man by Siegfried Sassoon, The Great War and Modern Memory by Paul Fussell, War Horse by Michael Morpurgo, and Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woof. In this same stack are two volumes of Ernest Hemingway: In Our Time and The Old Man and the Sea, as well as Fitzgerald and Hemingway: A Dangerous Friendship by Matthew J. Bruccoli and The Man Who Wasn’t There: A Life of Ernest Hemingway by Richard Bradford, a book which makes a case for the lifelong assholery of Mr. Hemingway.

On the shelf second from the bottom, moving from left to right, are books lately read. The End of Michelangelo by Dan Gerber (poems), The Spy Who Came in From the Cold by John Le Carre (too long neglected), The Last Wolf and Herman by Laszlo Krasznahorkai (perhaps I am a little late), and Let Me Tell You What I Mean by Joan Didion (to clear the head). Clustered and cluttered across the top of my desk are present and future readings. The History of Jazz by Ted Gioia, Homo Irrealis by Andre Aciman, Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer, The Vagabond by Colette, Grand Hotel Europa by Ilja Leonard Pfeeijffer, and Lartigue: The Boy and the Belle Époque by Louis Baring. That’s enough books to start a year.

Today, in fact, is New Year’s Eve. People will celebrate, while I will pretend to clean my office. In the shower earlier this morning, I kept thinking about a terra cotta vessel deposited in the courtyard of the house where I stayed this past summer. I knew the office and books needed straightening, but thinking about the vessel, I began to imagine what it had looked like from other angles. I imagined, for instance, what it had looked like when I walked down the stairs, leading from the apartment to the courtyard. I pictured how sunlight had tempered the vessel throughout the day. My thought was that, by seeing the vessel from another angle, it would perhaps surrender its stories to me, but it did not. Instead, I recalled the two tin lamps set side-by-side in a subtle alcove carved into the courtyard wall, just at eye level where the stairs either began or ended, depending on where you are going.

I turned off the water to the shower—this after maybe five or seven minutes of being wet—yet I was still in search of objects and their stories. Some of them I could see. There was May-Anne’s egg basket sewn together from birch bark. Also, Carl’s box elder orb that he spun on a lathe inside his magical woodshop, and a house in the woods where not a single object inside of it was made of plastic or glass. I remembered a stone inside the home of a Montana collector that had been used to crush berries for so many generations that the stone had been reshaped by the fingers of those women had who had worked with it, carried it, protected it. There was Tabby’s magnificent living room table and her collection of artbooks thereupon: Francis Bacon, Modigliani, Morandi, Sudek, Rutenberg, and others. Megan’s kitchen window that holds the view of the old barn and the way down to the fields and the woods that grow beside the road there.

Stepping out of the shower recess, I took the corner of my towel and rubbed a small aperture through the condensation on the bathroom window. Cold as it is, it doesn’t take much for the bathroom to sweat. In this collage of objects and memory, I needed to know what was outside or at least affirmation of what I believed was outside. The snow, the cold, the sea down below the house where the waves curled and broke and folded back into themselves.

It was a new year, almost, and I was a naked man standing between the world outside and undiscovered stories. As the waves went on folding and folding with the thought of someone’s table, someone’s stone. From the outside, the lights surely seemed bright, though the office needed attention. A minute more, and I could do that. Turn off one light, then click on another.