Summer comes slowly to the far north. Cold days peel into months, and the world stands tarnished with greys and drab olives. A day arrives, usually in June, when the grass is green, the peaks across the sund are capped with a cobalt sky, and the light is unflinchingly radiant and clear. It is the light you cannot forget. On the shoreline below my house, stones are rounded again with shadows and light. Gaps between the boards on nausts can be counted from a distance. It is the sort of light that when you are outside you look at your own skin, rubbing your arms as you do, to see if you, too, are covered by the light. I think about the late Classical scholar Maurice Bowra, who suggested that the quality of sunlight and how it struck the mountains and sea in Greece affected the minds and actions of those ancient peoples. If the topographies of deserts and tundra can shape peoples, then why not the sun?

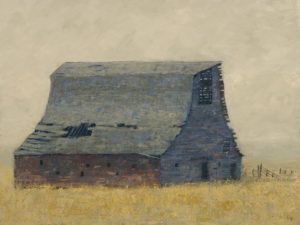

The path that starts across the road from my mailbox leads past an old sheep barn. I have written about this barn in other essays, and I am not sure why I come back to it or what about the barn retains my attention, though I suspect the barn holds stories that I’ve not yet heard. Traveling west of the barn, the path winds its way up a hill and into a wood of young birch trees and stunted juniper. There is a ruin of dry stone that I must cross before going up the hill. What remains of the wall forges eastward through the valley and vanishes into the trees nearest the road. But my direction, and the way the path travels, is uphill to the top of a ridge that separates the seaside valley where I live from the next valley over, which is flanked by mountains. There are birch trees on either side of the path until it tops out on a ridge. In summer, the trees are dressed with leaves and sunlight. The sight of birch trees in early summer makes a body feel lighter and makes me hyper with looking. There is new life on the ground, new life in the sky, and in the sea, on the mountains, on the branches that scrape against me when I walk, and in the fields and crops of hay that lie like quilt patches over the next valley. Here is a place of abundance or of abundance returned, and I must convince myself to be still. But I am overly anxious to see everything. I am overly anxious to take everything in.

On a walk this summer, I decided early there was no place I wanted to go. The top of the ridge, the next valley over, the high mountains—these are places where I could have gone, but I had no plans to reach them. I am trying to practice walking with no destination and, paradoxically, to be still while walking. This practice has not come easily for me. For most of my life, I have insisted upon a destination. Growing up, I made scores of walks in the canyon country of the Southwest to see overlooks and arches, to look at ruins, to see petroglyphs. Yet a walk in the woods (or desert) more often than not meant a walk to anywhere I could hunt or fish. I was not very aware of this part of myself until I was in my late teens, when I was out on a six-day backpacking trip in Southeast Utah. I was with a group of high school students and teachers.

One evening while we were sitting around a campfire, my former 11th grade chemistry teacher, Mr. Olsen, said to anyone listening, “I don’t know about you guys, but this hiking for hiking’s sake is for the birds.”

As cliché as that sounds, those were Mr. Olsen’s words, but soon afterwards, he glanced at me and said, “I would much rather be hiking someplace where I could catch a fish or shoot a deer. Something anyway.”

I nodded in agreement, yet I remember feeling then that I should have nodded along with Mr. Olsen, which is to say I was expected to nod along. Given my home town reputation as a hunter and fly fishermen in those days, it felt almost necessary that I should agree. The fact was then, that I often went outdoors to hunt or to fish. That’s how I explored places. But not always, I told myself, not always. Mr. Olsen went on to reminisce about dream filled lakes that took three days of hiking to reach, and every lake, predictably, was full of gigantic cutthroats. He talked about a meadow where a bull elk could reliably be found on opening morning, but to reach that meadow, he assured us, took two days of hiking “straight uphill, and I mean straight uphill.” I can see Mr. Olsen’s hand set at a 45’ angle, pushing upward as he described the hike for us.

I knew well these sorts of stories Mr. Olsen told around the campfire. I knew those utterances of cutthroat lakes and clearings where bull elk strolled about in some prelapsarian splendor. It was the sort of talk that I had listened to and engaged in practically all of my life, or at least from the time I had made my first fly cast at nine or ten years old. Yet there was something oddly public about that occasion. Publicly I agreed with Mr. Olsen, but privately I admitted that a walk in the woods didn’t need a purpose beyond itself.

All those summers years ago…. I occasionally think about them and realize that sometimes we all live between our years.

After I topped the ridge above my house, I headed west towards the sun. The sun had returned at the end of January between the V in the mountains across the sea, but it wasn’t until late February that I began to notice the lengthening of days and how the sun felt a little warmer. I could absorb this warmth through the windows in my living room and kitchen. There were hints of its warmth when I walked outside. Having been raised in the Southwest, I learned early in life to give attention to the sun. The sun in the desert can damage a body. Sun burn, dehydration, sun stroke, cracked lips and splits heels, these are real risks. Yet in winter, the sun can feel strangely cold. I did not understand this as a child. How could the desert sun cause 110’ temperatures at one time of year and feel frigid at another time of year? The answer came later. In the far north, the sun is another presence, and we celebrate our sun-filled days here. Sun and light are not to be taken for granted.

The ridge between the valleys rounds itself into a couple of hills before descending to the sea. When I came to the top of each hill, I searched for places where I have made fires. I try to make fires, if I make a fire at all, in the same places every year, but it can be difficult to find those places. This makes for a good fire. A good fire is one that warms and comforts and then disappears. On this afternoon, the view from the hills, coupled with sun and light, glossed the very substance of gift. I searched for where I had built fires but found instead healthy blueberry bushes and stems of multebær. The ground where I had built fires has become ground where I will pick berries.

Assuring myself that I would find them again, I looked up from the berry bushes and the mix of scattered stones and tinder. I will come back in August, when the berries have ripened. For now, the country before me spread lush with color, lush with summer. The sea appeared clear and blue, and I could see far away islands. I turned around in slow, uneven circles, taking in as much of this northern country as I could. There was too much present, too many returns. I was the clumsy middle age man turning about in a world. The sun and light and a thousand returns meeting this man, lifting me, breaking me, granting more life. And when I stopped turning, I stood facing the west and facing the sun. I tilted my head back, and the sun fell full and warm on my face. I took deep breathes and waited until I vanished. Then I walked on without thinking much, taking my way along the thin trail that enters the next valley, ending at the road and the sea.

Later that evening, I made a few notes in my journal, just a few. How the berries will do this year. How the sun felt. How I questioned again if the best days could last in our clipped eternity, then would they still be the best days?

I am not aware of all the ways this world is shaping me. Some things are obvious, such as how walking here has conditioned my body and that I have become more tolerant of cold and that I notice how the experience of sunlight has become a moment of mercy or release. These things I recognize. I believe, too, that landscapes open the heart. They open the heart similar to how a painting can open the heart. We see as much as we can see. We go with them as far as we can go, knowing there is no prescribed place where we will stop and where they will go on. We have walked together, and something has been given.

*This essay is a selection from Between Artists: Life in Paintings and Prose, and is also available on Juke. If you are a paying subscriber to Juke you can listen to Damon reading the full 10 minute piece on their site.