“At Work” is a sequence taken from a larger collection of vignettes and images put together by me and the photographer Wes Kline. The collection is called 18 Fragments. Our collaboration began in late 2020. At that time, I was catching a bus every morning and riding it to construction sites in the city. The city is about an hour from where I live.

I am not a construction worker, which is to say I do not have the skills of a carpenter, mason, plumber, roofer, or a dozen other jobs required on construction sites. What I can do is pick up garbage and move materials wherever they need to be moved. It’s mostly thankless work, which I don’t mind. People tend to leave you alone when you pick up trash. There can be hours to daydream, too, considering the slow distance between the fourth floor and the metal container when you’re carrying safety clamps.

There are also the people you meet. Men arrive from Poland, Spain, Lithuania, all over Europe to grab a job here. All of these men have stories, though not all of them wish to speak. Circumstances can open some men and close others. At work, stories are how we form separate bonds from our companies and tasks. We learn about each other. We learn familiar words in other languages. I can say ‘fuck’ in Polish two different ways, for instance. We learn about certain intimacies, like of the Portuguese foreman who told me he sent most of his earnings back home where his daughter took dressage lessons. These stories feel necessary, and I wonder if they are something of what keeps us from going under an inch at a time.

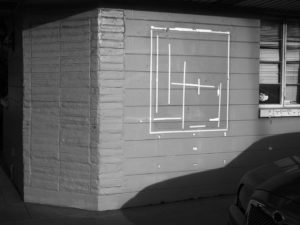

This is a part of what Wes accomplishes with his photographs. I say part because like any decent work of art, there is more technique, feeling, and expression in Wes’ photography than a couple of glances will give us. I have looked at Wes’ photographs for a few years now, and I go on seeing mythologies. Weeds sprung from concrete blocks may be the tendrils of some goddess. Unexpected geometries may map a way to the underworld or suggest another bend to spend time with. And we should take time with these pieces. They are, as the chewy phrase goes, at hand.

Since we are late in the year and in the dark time, we do not see the sun and will not see the sun until the end of January. People leave their curtains drawn back from their windows and the lights turned on, but on a Wednesday morning, I saw three bright windows on a block where all the other windows were dark. Three bright windows. I am not sure what struck me first. The fact of three bright windows or the fact that all the others were dark.

One Thursday afternoon two Portuguese workers said goodbye. They were returning to Portugal. One of them shaped his hand into an airplane, the way we do when we talk about flying, taking off with our fingers set straight but curling them before we land. Por-tu-gal, he pronounced and smiled. Por-tu-gal, I repeated. And for some reason I said to him, Vaya con dios. Si, vá com Deus, his friend corrected. Then we patted each other on the shoulder and nodded until there was nothing left to say.

While waiting for the bus one Wednesday evening, I met a Frenchman who had moved to the north because, as he told me, he loved the snow and cold. I asked him if it snowed much where he had lived in France.

“No,” he said, “we did not have snow.”

It was already 4 o’clock, and the bus to sentrum was late.

“But I miss the food. That is the one thing I miss. The food.” He shook his head and said, “Frutti di Mare,” then looking at me, “but no wine. I do not drink wine.”

A plumber told me that as a child he had lived on the banks of a famous salmon river. He said he had fished for salmon and trout all his life.

“A Montana Nymph,” he said. “This is the only fly a fisherman needs.”

I tried to tell him how some flytiers will use an orange thorax instead of a yellow one. ”They call it a Ted’s Stone Fly,” I said, “after the late sportsman and writer Ted Trueblood.”

“This is a very good fly,” he said, “but you must fish it with enough weight.”

What I did not tell him was that the Montana Nymph was the first fly I had ever fished with and this on a desert creek more than thirty years and four thousand miles ago.

Four thousand miles—the distance between here and there. But how many miles in thirty years? How many miles between a desert creek in Utah and a fly-fishing plumber who shares the same name as a god?